In which I remain aboard Teddy for the East Coast of Greenland, sailing through foggy iceberg fields, exploring poorly charted fjords, finding legendary anchorage(s), and reveling in the sublime at every turn.

The math checked out, I could stay aboard for Greenland and jump ship as Teddy passed Iceland en route to Clifden, with one day’s wriggle room to make my flight to Boston. Nothing ventured nothing gained. At 1530 on the 16th of July, Teddy cast off from Isafjordur with a belly of diesel* and water, and a crew of four: Nick, myself, Darren Johnston (an Irish-born Canadian), and Diego Lopez (Espana). With the yanmar purring sweetly we motorsail down the fjord, confident after multiple inspections that the stern gland is still providing a seal, despite the recent entanglement fiasco. We’re three-sailing before we leave the fjord proper, and put the yanmar to bed as we push off across a developing nor’easter. Teddy calls for her first reef before dinner is ready, we’re blast-reaching at roughly six knots on a magnetic course of 315-325, a good start to our passage to the ice. Both Darren and Diego are a touch green around the gills this first evening, so Nick and I divide the dark-less night between us, neither minding being topside in such ideal conditions. It’s rowdy enough to be interesting, and the odd spray to the face keeps one awake as we barrel along, a moderate fog dampening our outlook. We back the staysail around 2200 to slow us and ease the motion for sleeping crew, although onward progress is maintained at a very pleasant rate.

*Good Icelandic diesel. The diesel in Ireland contains a certain percentage of biodiesel; good for cars, but very prone to contamination when sitting in a boat tank for prolonged periods. We left Clifden with less than full tanks in order to capitilise on the cleaner stuff up north.

With the sea and wind progressively dropping throughout the early morning, we lean into the familiar and comfortable passage-making rhythm. Multiple coffees, pages of good books, conversation both enlightened and inane. All of thus rudely interrupted by a urgent cry “ICEBERG AHEAD!”. No snoozing now; not more than thirty hours out of port and we’re being formally welcomed to the Arctic by a most polite advance guard. A low, flat berg wallows into view on our starboard bow, bobbing languidly in the easing swell, the telltale turquoise highlighting the protruding spurs below the waterline that could turn a polite encounter into a titanic event for a lesser vessel than Teddy. We maintain a respectful distance, best to play it slow in the early stages of this relationship. There’ll be plenty of chances for more intimate contact in the days to come. Icebergs at sea are new to both Darren and Diego, if more familiar to Nick and myself (Greenland and Antarctica respectively), nevertheless the first sighting is exhilarating. Like children (allegedly), the first iceberg always gets a disproportionate amount of attention in comparison to it’s later siblings – oohing, aahing, and innumerable photographs heralding it’s arrival. Complacency tends to set in after the hundredth berg or so, with newcomers really having to work hard to impress the onlookers. It is a testament to the seemingly infinite variations in size, form and colouration of bergs that one is never truly used to, or bored of, the views amongst the floating sculptures. Although small and low-lying, this first berg has it’s own story to tell, flat surfaces oriented non-horizontally showing previous waterlines prior to melt-induced rollovers.

We don’t see more bergs until 1330, after which we can almost be guaranteed to see some ice at some point of the horizon. Guaranteed given good visibility, that is. By 1700 we’re well inside the Arctic Circle (at 67 15.212 N, 28 23.933 W), and we’re fogbound, the restricted vision all the more evident thanks to the psychological warfare wrought by the knowledge that we are sharing these waters with multi-hundred tonne chunks of very solid ice. With no radar to extend our electromagnetic perceptive capabilities, we’re down to first principles and the holy trinity: good eyesight, a responsive helm, and solid steel. At least fog and strong breeze are rarely bedfellows; any incidents will be at a leisurely pace. Faith is not needed much longer, as the fog lifts progressively to reveal an oh-so-sweetly shining sun. And mountains. Mountains? Mountains to the north. A check on the charts shows land to be over sixty miles away, revealing two facts. One, the air is very clear. Two, those mountains are fairly substantial. The first impression from such a distance is a barrier of harsh, raw and geometric peaks, speaking to a rather desolate yet beautiful landfall. While a new view, the geometry is familiar; bare granite slabs that represent the resistant remnants of old planetary crust subjected to many millennia of glacial assault. Onward, Teddy, onward!

Around 1900 a proper sized berg looms over the horizon, easily dwarfing Teddy’s 49′ main mast by another fifty percent, and glowing with the eerie iridescent blue that seems internal to many larger blocks of ice. The bulk of the berg has further effects. Like any massive body, it exerts a gravitational pull, drawing Teddy and her crew closer and closer. Well within the “splash zone”, we gaze up in awe at this lumbering behemoth, captivated by the implied time and distance traveled by the pristine ice crystals which originated as fallen snow somewhere in the Greenland interior, some time ago. As we leave the berg astern, we are given a gentle reminder as to the realities of the region we are entering. Little more than a hundred yards behind us the berg begins to roll, seesawing through sixty degrees or so for several minutes, sending cattle-sized blocks of ice thudding into the water, most significantly the water most recently occupied by Teddy and ourselves… A timely reminder to beware of beckoning beauty, and perils hidden behind the allure.

I’m on watch from 2200 to 0100, but miss the sunset due to the return of a pea-soup fog. What ensues is the most eery and surreal sailing of my life to date. On a broad reach with a 1-2 foot following sea, Teddy is gliding along a slick sea at 4-5 knots, while I continually scan the four-boatlength perimeter for encroaching ice. Totally silent except for the occasional flutter of the genoa leach, and the gentle gurgle of rudder wash, it’s both sublime and fatalistic. If there’s a berg ahead I should see it before we hit it and, excepting a monstrous glacier-spawn, four boat lengths is enough room to complete at least a ninety-degree sidestep (either hardening up or throwing in a quick gybe). All else is out of my control, and there is nothing more to do but stay alert and enjoy the ride. As perfectly meditative and devoid of distracting internal chatter as I’ve ever experienced. Perhaps it’s the ever-looming possibility of peril that sweeps the nonsense from the cranial corners more effectively than any breath control exercise has managed to achieve?

I’m woken just after 0400 by the yanmar ticking over. A slight interruption to our planned blissful sail into the fjord. Nonetheless, a cursory peek out the companionway is all that’s needed to tell me I won’t be sleeping any longer this morning. The view from the cockpit is intoxicating, captivating, and totally stimulating. A two-tone barrier of rock and ice occupies the entirety of the horizon ahead of us, stretching north and south in a seemingly impenetrable jagged wall. We’re over 25 miles out from the fjord entrance, yet the peaks are already imposing in their majesty. The new day is sublime, a flat sea basking under a warming sun, although a little more breeze wouldn’t go a miss. As we search for our gap in Greenland’s toothy welcoming grin, we are distracted time and again by whale spouts, glaciers, and berg after incredible berg. Each piece of ice moves to it’s own rhythm, like ravers at a silent disco; some appear still, others others rock from side to side, while neighbours bob up and down vigorously, each being led by currents at different depths. If not for the yanmar’s throaty purr, the assumed silence would be shattered by the symphony that is living ice. Cracks and pops sound from every direction, drips of metronomic meltwater hold time, and enormous booms resonate from afar as unseen glaciers give birth to their white coated calves.

The topography and hydrography of the Greenland coast has not yet been accurately placed within the geographic net to date. As such, GPS derived positions do not agree with charted positions (e.g. – triangulating bearings from topographic features), having potential for considerable navigational distress. Parts of the northern and eastern coasts may be displaced by up to 5,000 m (this displacement not necessarily being regular or extrapolatable), meaning a plotted GPS fix could well see you high and dry in a mountainous region of your chart(s). Further, detailed bathymetric data are extremely lacking, with reported depths often restricted to a single track of reconnaissance soundings. All charts on board are thus covered with appropriate disclaimers as to their lack of suitability for navigational purposes. Handy that.

So passes the most pleasant of days, wending our way up the fjord between uncountable bergs of every description. Glorious sunshine and a slight breeze both fill the sails and stretch the smiles all around. The ease of our passage and approach has a more serious implication however. As recent as 2004, cruising guides suggested the East Coast of Greenland to be un-navigable until at least mid-August (some years not at all) due to high ice concentrations flowing south in the East Greenland Current. We’ve breezed through with barely a waver off our rhumb line. A single/anecdotal data point sure, but indicative nonetheless. The National Snow and Ice Data Centre have excellent summaries of the 2019 summer effects on both Ice Sheet mass loss and Arctic sea ice extent.

Finding a suitable flat, low, and presumably stable berg, our minds turn to conquest. At idle Teddy coasts up to the new world, as I dangle off the bowsprit. As the bobstay contacts the ice I (gracefully) depart, to claim berg for queen (Teddy) and country, as Nick backs off to leave me to my mutinous meanderings. Darby joins me shortly after, and we stroll leisurely across our floating kingdom, brewing plans for further commonwealth colonial expansion. But the skipper will have none of that, we sail under an American flag after all! Climbing back aboard is less graceful than the dismount; soft rubber boot soles are great for textured deck paint, less so for sloping melting ice. Hilarity ensues for those already aboard.

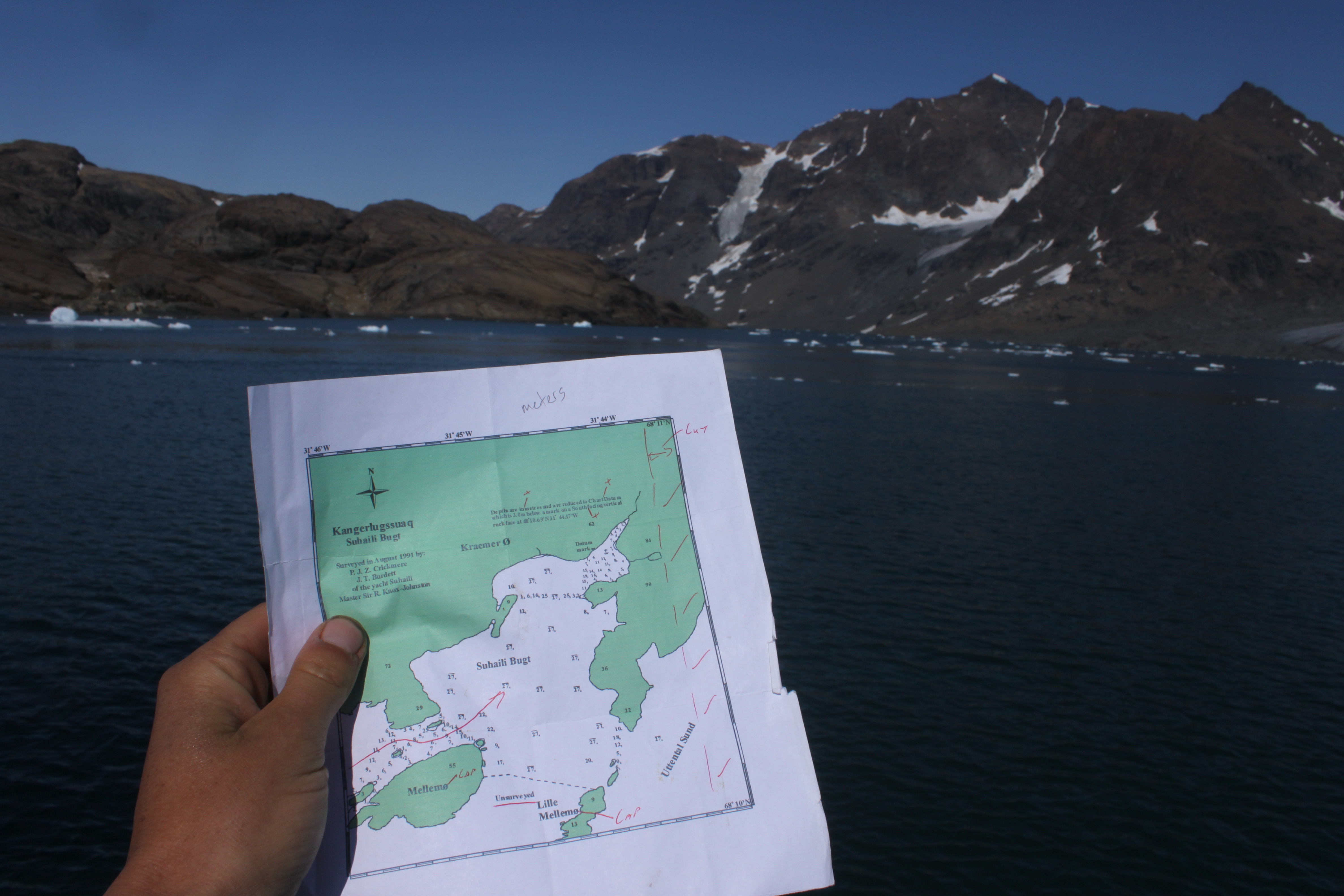

While the official charts may be of little use now we’re within the fjord, we do have some pilotage charts from a rather experienced sailor – Sir Robin Knox Johnston. In the summer of 1991 Sir RKJ and Chris Bonnington mounted a climbing expedition to Kangerlugssuaq Fjord, sailing the infamous Suhaili from the UK to East Greenland to bag a couple of peaks. An account of this expedition can be found here. The anchorage they chose to leave the vessel in, on the southern side of Kraemer Ø, was dubbed “Suhaili Bught”; a hand drawn chart of this, with soundings and a datum mark noted on the rock face, was provided to us by Mike Henderson of Pangey, only one removed from RKJ himself.

As we close on the anchorage, navigation gets more and more challenging. With two in the shrouds keeping an eye out for colour changes and currents indicating a rising floor, we wend our way through the berg field. By sticking closer to the larger bergs as we get closer to land, we ensure a suitable depth beneath the keel. If the bulk of an iceberg is below the water line, a berg with three foot of freeboard should be indicative of at least two fathoms draft. A line-up of similar sized bergs is taken to indicate a bar or shelf grounding them in place, and thus a possible obstruction to our progress. The water is crystalline, and the sun blankets us in warmth and good visibility. Drifting in the vicinity of Suhaili Bught, we try for fish and have a beer on beck, as steep glaciers cascade down rock faces all around us. Eider ducks bob around us, rousing thoughts of future meals, and a timid seal keeps an eye on us, spyhopping from a distance.

We carry on pass the knight’s anchorage, and push up Uttendal Sund towards the back entrance to Watkins Fjord. Constant leadlining fails to touch the bottom in this un-sounded sound, as we take in the sensational vistas; peaks reminiscent of Patagonian scenes fill our periphery, and the yanmar’s chug reverberates off vast granite walls. We are spellbound, hypnotised by the grandeur of raw slabs of rock, with vast ice rivers clinging to their impossibly steep slopes. RKJ’s target peak was called The Cathedral, and it’s easy to see why; nothing short of worship and awe is possible in such a setting.

The back-door is blocked by a row of icy bouncers, and we turn tail to find a spot to drop the hook. Going further south of Suhaili Bught, we circumnavigate a small islet to approach an abandoned village. Currently at the peak of a three metre tidal range, we’re happy to find a muddy silt bottom in six fathoms, some fifty metres from a steep-to shore. Grounded ice to both east and west of us flag good protection from shoals, there’ll be no giants rubbing against us here. I row a stern line ashore, there is less room to swing than our scope would like, and I set first foot on good Greenlandic granite. We’ve arrived.